Optimal Design of Investment Committees (2023)

Bernd Scherer

The Journal of Asset Management, URL/SSRN

After a long break of almost exactly 3 months – I had several other tasks that required my intellectual capacity – it is time for a new AGNOSTIC Paper. This one examines the design and challenges of investment committees (ICs). Even more important, the author suggests a simple and powerful solution for some of their most common challenges. As someone who regularly enjoys the process of committee-based decision-making, I believe this week’s paper is quite powerful and offers a lot of valuable lessons for both investment managers and their clients.

Everything that follows is only my summary of the original paper. So unless indicated otherwise, all tables and charts belong to the authors of the paper and I am just quoting them. The authors deserve full credit for creating this material, so please always cite the original source.

Setup and Idea

Without having specific data to support this statement, I would argue that most institutional investors make their decisions via some type of investment committee. There are endless variants, but the ultimate goal always remains the same. You want to aggregate the views of your most experienced and skilled professionals into one overarching consensus. As in most other disciplines, a combination of smart people should deliver better outcomes than any single one of them alone. Some ICs decide by majority, some have a dominant Chief Investment Officer (CIO) who listens to different opinions and aggregates them more subjectively, and a lot of them are probably somewhere in the middle of this spectrum. In addition to the supposedly better decision-making, transparency and accountability are also important reasons for ICs.1In my opinion, the question whether ICs actually generate better outcomes is very interesting. They certainly narrow the range of outcomes. Most likely, you will not be ruined by the crazy idea of a single trader with a convincing personality. On the other hand, you will probably also not invest with some of the rare investment geniuses. Ask the shareholders of Berkshire Hathaway (URL) if they would trade Warren Buffett for a 10-person IC and I can tell you the answer. Admittedly, however, there are very few Warren Buffetts in this world… As you can see, it is not so obvious and the question is probably worth a post for itself…

Overall, ICs are a relevant and very common feature of the investment industry. I therefore fully agree with the author that they are worth studying. Making good investments is the one and only job of asset managers, so having effective decision-making processes seems like a competitive advantage. At the same time, it is also relevant for clients to understand how and why their managers make decisions about their money.

Data and Methodology

The paper is a mix of personal experiences of the author, theoretical considerations, and takeaways from behavioral finance and economics (URL). As a result, there is not much data or methodology to present at this point.

Important Results and Takeaways

Good theory: ICs ensure the same quality for all clients

Before coming to the challenges, the author first argues that ICs are generally a good idea. The underlying principle, as often, is diversification. According to the author, decisions of experts inevitably come with a certain degree of noise. It is the job of an effective organization to remove as much of this noise as possible to ensure the same quality for all its clients. It therefore seems better to aggregate the views of several (hopefully) skilled professionals in an IC than to select just one of them.

The author also supports this with some arithmetic from the world of investment management. Suppose you have an asset manager with 10 portfolio managers (PMs) who each manage a separate fund and do not interact with each other. Further suppose that those PMs have skill and can generate an information ratio of 0.20. Such an information ratio, according to author, comes with a 57.93% probability to outperform the benchmark in a given year. Sounds great, doesn’t it? A company full of skilled PMs and a better than 50-50 chance to outperform.

Yes and no. Yes, because the professionals do have skill. No, because a successful asset manager should strive to deliver consistent performance to all of its clients at all time. Since the PMs do not interact with each other, clients of this hypothetical firm effectively play a PM-lottery. Yes, they have a higher chance to outperform than to underperform. But the chance that all PMs (and thus clients) of the firm simultaneously outperform is with 0.43% very small.20.579310 for the theoretical case that all PMs are truly uncorrelated with each other. This is of course unlikely in practice, but I think the assumption is okay to illustrate the argument. Admittedly, it is even less likely that all PMs simultaneously underperform (probability of 0.02%).3(1-0.5793)10 when all PMs are uncorrelated to each other. Over the long term, however, basic probability calculations tell us that only about 57.93% of clients outperform each year.

This is as if the quality of your iPhone depends on the person who manufactured it and just over half of all customers are happy with their phones in any given year. In danger of stating the obvious, this is not what you want to have as a successful firm. Every customer should receive the same high-quality iPhone at any time and it is the job of Apple to guarantee this. The same applies to asset managers. You want to deliver the same investment quality to all of your clients at all time and use the skill of your professionals as good as possible.

So let’s see how the example changes when the 10 PMs aggregate their views in an IC. If the skills of the PMs are truly uncorrelated, which is most likely not true in practice but okay for this example, the aggregate information ratio increases to 0.63. The probability to outperform the benchmark increases to 73.65%. This is of course better than 57.93%, but there is a trade-off.

If you only offer one instead of ten investment processes, your firm either outperforms or not. There is no longer a chance that you have a few lucky clients who got the annual outperformers by pure chance. Either all clients outperform or no one does. All clients receive the same iPhone at any time, no matter which employee manufactured it. By consequence, all clients also suffer when the iPhone comes with poor quality. This is in-line with equal treatment of all customers, but naturally puts pressure on firms to maintain their standard of quality. The author argues that this is what successful firms should strive for. This speaks for centralized decision-making and ICs are (theoretically) a useful tool for this.

Another interesting aspect is the signal to clients. Firms that dare to committ on one overarching investment strategy show their clients that they actually believe in the skill of their professionals. In the first case, the chance that all 10 PMs simultaneously underperform is with 0.02% very low. As a consequence, you will have at least one outperformer that you can print on top of your marketing material in almost every year.4Probability that at least one PM outperforms: 1-0.02%=99.98%. In my experience, this is unfortunately a very common strategy among asset managers. Launch a couple of unrelated funds and you will most likely have an annual outperformer by pure chance… In the second case, this is different. Either your strategy works and all clients outperform with the higher probability of 73.65%, or it doesn’t and all clients underperform with an also higher probability of 26.35%. Only firms that can actually deliver a high probability of outperformance can afford to follow the second path. Firms without skilled professionals and/or effective decision-making processes therefore have an incentive to rely on the PM-lottery to have at least some happy clients by pure chance.

From my own experience in manager selection (URL), I can confirm that there is a lot of truth in those considerations. I and many other manager selectors I am speaking to favor organizations and investment teams with a clear and unique strategy over the random Star-PM.5I don’t say that Star-PMs are bad. Individual genius certainly exists, but it is very hard to find. I also believe a team of skilled PMs with effective decision-processes is better than any single one of them alone. The author further supports those arguments with references to empirical research that shows better performance for team-managed funds.

Overall, there are good reasons why centralized decision-making makes sense. Successful firms should offer the same investment quality to all clients at the same time. Since only firms that actually believe in their investment skill can afford to committ to one unique strategy, centralized decision-making can be an important signal for clients. All of this speaks in favor of ICs. On the other side, there is the possibility that ICs suppress individual genius and yield worse outcomes than that of your most skilled professional. By definition, however, genius is rare and centralized decision-making is probably the better option for the vast majority of firms.

Bad practice: ICs suffer from psychological biases

In practice, effective group decisions unfortunately face a lot of challenges from human psychology. Inspired by the book Noise: A Flaw in Human Judgment (URL) by the just recently passed Daniel Kahneman, the author highlights several well-researched human problems in a committee-setting.

The first, Group Shift Bias, is the phenomenon that group decisions can drastically change depending on how information is presented. When the CIO as highest-ranking member speaks first, this will probably have an impact on less-senior members even if their actual views do not change. Another aspect is Group Polarization, the tendency that groups make more extreme decisions. If most IC members argue in favor of US equities, the minority with different views might just follow the rest to avoid the discussion.

Another famous psychological bias is the Disposition Effect, the tendency to hold losers for too long because of loss aversion. The author argues that ICs also suffer from this bias as humans naturally manage their reputations. Depending on the firm culture, admitting mistakes is clearly difficult. Who is more likely to get promoted? The (over-)confident person who highlights his past successes or the quiet one who logically explains the flaws of previous decisions and advises to close positions before even more losses accrue? Of course, it should be the second one. I am quite confident, however, that reality is sometimes very different.

Incentives of individual professionals also often interfere with effective committee decisions. Depending on the size and structure, the individual impact on committee decisions is small. In addition, most companies reward individual performance and employees optimize accordingly. This can lead to a Free Rider Problem. Some members of the IC may just subscribe to the current consensus and avoid the effort of forming own opinions. No one can punish you for apparently having the same opinion as the previous speaker. As long as you don’t have to open the committee, free-riding is therefore a pretty viable strategy.

Finally, ICs come with various Coordination Costs which tend to increase exponentially in size and sophistication of the committee. I think this one is quite obvious and most people agree that 10-person meetings are more than twice as worse than 5-person meetings.

Solution: Anonymous member-portfolios

To deal with the challenges, the author suggests an (in my opinion) simple but powerful solution. Instead of long discussions with all kind of psychological issues, each IC-member submits an anonymous model-portfolio before the meeting. To aggregate the views of all members, the IC then simply averages the position weights and scale the portfolio to the desired context.

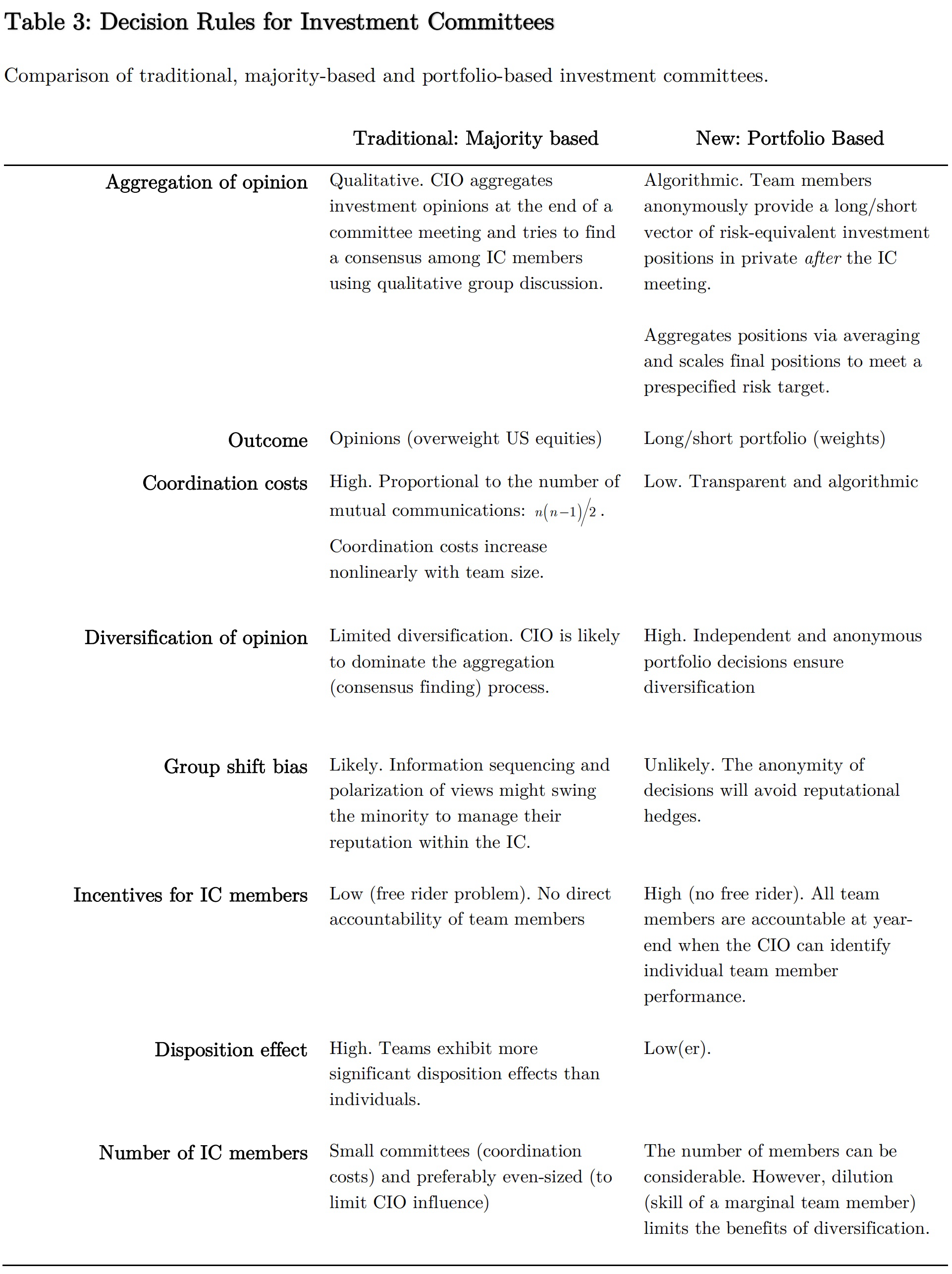

This approach mitigates all of the above-mentioned problems. There is no Group Shift Bias as all members submit their portfolios anonymously and before the meeting. The Disposition Effect is arguably still an issue, but people are probably more willing to admit losses and mistakes anonymously than in a group discussion. Incentives are fully aligned as members must create a model-portfolio for which they are accountable and can receive compensation. And Coordination Costs are much lower because averaging portfolio weights is more efficient than long-lasting discussions. The following table again summarizes these points in comparison to the traditional IC.

Conclusions and Further Ideas

The idea centralized decision-making and ICs is generally a good one. In theory, it ensures the same quality for all clients at the same time. The traditional group discussion, however, comes with severe psychological challenges. From my perspective of a relatively young investment professional with not too much self-confidence, I can confirm many of the considerations and really like the idea of the anonymous model-portfolio. I also believe that even ICs that do not fully implement the anonymous portfolios can unlock significant value from the unbiased opinions of their members.

In one of his concluding paragraphs, the author summarizes his experiences with the approach as follows: “In my experience as CIO at previous firms, the portfolios submitted anonymously by IC members show a much more significant position variation than the communicated opinion difference in IC meetings. The average pairwise correlation between team members is typically low, and it was always difficult for me to imagine that I, as a CIO, could have unveiled this difference in opinion via a group discussion during or towards the end of an IC meeting. Since each IC member manages their long/short portfolio, a group disposition effect is much smaller.” (Scherer, 2023, p.133, URL)

Nothing is perfect and some may understandably argue that this approach is quite harsh. Committing professionals on the performance of their investment recommendations can lead to unwanted consequences like excessive risk-taking or blaming within the firm. On the other hand, if you are not willing to take responsibility for investment processes and results, you probably got the wrong job in the first place. Employees who do have the skill they pretend to have are probably happy with the approach, while employees who enjoy free-riding in the traditional setting are probably not. I do believe, however, that this approach requires proper leadership that considers the chaotic nature of financial markets and distinguishes between outcomes and processes.

Another key problem of the portfolio-approach is communication. It is probably easier to tell your clients “We overweight US equities because our CIO and members of the IC strongly believe in continuous dominance of the Growth Mega Caps.”, instead of “We overweight US equities because the average US weight in our anonymously submitted IC-member portfolios is larger than the passive weight in the MSCI World index.”. Rational clients should understand that the second approach probably leads to more robust outcomes. But if all people were rational, we wouldn’t need the portfolio-approach to mitigate the non-rationalities of group discussions in the first place…

- AgPa #82: Equity Risk Premiums and Interest Rates (2/2)

- AgPa #81: Equity Risk Premiums and Interest Rates (1/2)

- AgPa #80: Forget Factors and Keep it Simple?

- AgPa #79: The Momentum OGs – 30 Years Later

This content is for educational and informational purposes only and no substitute for professional or financial advice. The use of any information on this website is solely on your own risk and I do not take responsibility or liability for any damages that may occur. The views expressed on this website are solely my own and do not necessarily reflect the views of any organisation I am associated with. Income- or benefit-generating links are marked with a star (*). All content that is not my intellectual property is marked as such. If you own the intellectual property displayed on this website and do not agree with my use of it, please send me an e-mail and I will remedy the situation immediately. Please also read the Disclaimer.

Endnotes

| 1 | In my opinion, the question whether ICs actually generate better outcomes is very interesting. They certainly narrow the range of outcomes. Most likely, you will not be ruined by the crazy idea of a single trader with a convincing personality. On the other hand, you will probably also not invest with some of the rare investment geniuses. Ask the shareholders of Berkshire Hathaway (URL) if they would trade Warren Buffett for a 10-person IC and I can tell you the answer. Admittedly, however, there are very few Warren Buffetts in this world… As you can see, it is not so obvious and the question is probably worth a post for itself… |

|---|---|

| 2 | 0.579310 for the theoretical case that all PMs are truly uncorrelated with each other. This is of course unlikely in practice, but I think the assumption is okay to illustrate the argument. |

| 3 | (1-0.5793)10 when all PMs are uncorrelated to each other. |

| 4 | Probability that at least one PM outperforms: 1-0.02%=99.98%. In my experience, this is unfortunately a very common strategy among asset managers. Launch a couple of unrelated funds and you will most likely have an annual outperformer by pure chance… |

| 5 | I don’t say that Star-PMs are bad. Individual genius certainly exists, but it is very hard to find. I also believe a team of skilled PMs with effective decision-processes is better than any single one of them alone. |